The Beer Blog

Last update: December 4th, 2016Beer has been a part of cultured Humanity for thousands of years. At a time when the earliest records report commerce in trade on clay tablets in ancient Babylonia, people were already making 20 variations of beer.

Good brewing practices for the last 1200 years we owe to Charlemagne when he utilized the Church and Monasteries to teach people how to survive, how to farm, and brew beer in a methodical and safe manner. From this and the expansion of trade and rise of the middle class and industrialization, more than 100 unique types of beer are defined by culture, by history, by economy, by religion, and by celebration.

I am fascinated by beer and beer history. I am geeked on discovery of new beers, and concerned about quality, distribution, promotion, and of course production. This page contains a very brief record of my contribution to beer and history, worts and all.

Enjoy.

Briefly, as a young adult I didn't care much for the taste of beer. Even in the Navy; it was just weak carbonated swill. But this opinion began to change when I took a part-time job as a bartender during college and was exposed to several European imports with bottled Guinness Export becoming my first "favorite" beer probably because it was the diametric opposite of Budweiser. A couple years later I was working around in Santa Clara California and hooked up with a good buddy that enjoyed chasing down new beers on the market. At that time we just kept mental notes on what was good and when it went on sale - 😃.

Later I bought a home in Livermore-Tri Valley and started hanging out at local favorite watering hole Lion's Brewery of Dublin California. Through associations there I picked up some rudimentary knowledge of brewing. Publican Judy Ashworth (BJCP-National judge) taught patrons how to appreciate beer through a "passport" system where the imbiber would record the character notes of each beer long before there was Internet and Taphunter.

The adventure in homebrewing began immediately following Super Bowl XXIV (1990) when the San Francisco 49ners beat the pants off the Denver Broncos in a ridiculously lopsided 55-10 win: My beer buddy shared an impressive Belgain-style homebrew of his during the game, and the next day he taught me how to make a basic pale ale using extract malt.

We drove to this little odd shop in Morgan Hill that sold coffee, tea, spices, kitchen knickknacks, and beer & wine supplies + deli sandwiches. The gal that ran the place was very nice; we gave her the recipe and she proceed to fill our bucket with slow-moving liquid malt extract. She asked if we wanted a beer & a sandwich while we waited for this process and we did. After about 10 or 15 minutes, she says "how many pounds of malt did you want?" And my pal says "five", and as she cuts off the flow with a knife and weighed it, she said "well, you got six". Such was the accuracy in that day – 😃. I will never forget the first time I took in the wonderful aroma of malt boiling; it had me salivating in anticipation and made hungry to want of more.

A month later I would try to do this on my own, solo. Today I know that first batch was horribly flawed, but still liked and shared it. I persisted and in two years was making pretty good-tasting beer that everyone could enjoy mainly by doing a lot of reading, upgrading to better equipment, and perfecting my skill. Teaching other people also helped to focus communication on what is most important: start with a good recipe, use quality ingredients, attention to sterilization and cleanliness, fostering a stable brewing environment, avoiding oxidation, and careful handling of the finished product.

I went through several phases of brewing equipment as well, learning in the hard way what not to use, such as eliminating beer from contact with wood and plastic elements wherever possible because they provide safe harbor for bacteria. By the time I moved to Redmond in 1993 my second 3-tier RIMS (Recirculated Infusion Mash System) was already designed, based on ½ barrel starting capacity, and could easily output 13 gallons in about 4 hours with a double-batch following after just 90 minutes if one was so inclined. Between 1990 and 1996 over 100 batches were brewed and recorded, the majority in concert with friends.

Some recipes went terribly sideways, like trying to make an "Apple Beer": The first time, I used real apples, pureed and added into the plastic fermenter. Three days later little white rods are flowing in the thickened mass and the stench was most unpleasant. I called my Uncle for advice; he said "bring it up here and we'll distill it" but there was no way I'd risk spilling this in the car; I'd have to torch it to rid the smell. Instead, I poured it down the storm drain – and the neighbors complained. Lesson learned: Always pasteurize your fruit! 😃

The next time I used an Apple Extract – which caused horrible gushing and foaming, and had developed odd other faults. Lesson learned: Don't trust extracted flavors; better to use real fruit. The third and final time, we made an apple beer using real pasteurized fruit, but again we had the foamy problem plus cidery off-flavor (caused by too much fruit in the recipe). Coincidentally we had also made a "Spruce Beer" using fresh new spring growth, but we added too much and the beer tasted like Pepsi. One of my pals who had no sense of palate whatsoever but was always ready to acquire any free beer we were willing to dispose of – took on a lark a pint glass and blended the flawed Apple and Spruce beers together, and the admix was very drinkable… who would have thunk?

On the flip-side, there was one recipe that had entirely vexed me during the production and I was certain it would become my greatest failure. I was trying to replicate a German-Style Weißbier by using decoction: A portion of the mash is cooked separately then added back to the main mash in order to raise the temperature and facilitate faster conversion. Wheat malt in particular is low in enzymatic power compared to barley malt, and decoction is the way the ancients have been forcing conversion of starch to sugar for centuries. In my process on this day, I had first pulled ¼ liquid and boiled it, but it didn't raise the temperature enough, so I took ¼ grist from the mash and cooked that but it too did not raise the temp sufficiently. I did this two-step method 2 more times (liquid then grist) before the thing had come out where I wanted it after a marathon of 9 hours. I was completely exhausted. Into the fermenter it goes without much hope, and later I kegged it off and set it into the back of the fridge. Weeks, perhaps months go by and I rediscover this beer and pour a pint for myself and my Brother-in-Law: It was crystal clear, brilliant golden-pale, with a persistent white rocky head and lace. My BnL who mainly drinks only Bud or Coors was blown away! It came out as one of the top five beers I have ever made, but sadly there was only 5 gallons of it.

People ask me what is my favorite style and I always answer: "All of them". There is one though that I like to make most often because so many commercial brewers don't know how to make it right, and that's (as you might guess) Fruit Beer. I like to make a low-gravity low-alcohol (about 5% abv) wheat beer, let that ferment to about ¾ of the way through, then rack that onto a fruit base, such as Blackberry, Marionberry, Lingonberry, Cherry, and Raspberry. The alcohol gain is about ½% but that's not the point: I just like a nice refreshing session beer for the summer and fruit beers do it for me. The trick though is you must use fresh fruit and not be too stingy about it. The wheat base provides a nice body without being too thin or chewy, plus the hops are managed low so we can enjoy the real fruit bouquet. My other fermenting predilection is New England-style Cider but that's another topic altogether!

It was a lazy spring Friday afternoon just after lunch in 1995 working at Microsoft. At that time there were no email filters or auto-routing; it all came into the INBOX. I belonged to the "Homebrewers at Microsoft" social group at a time when Contractors still had access rights to typical niceties. One guy posts a funny thread with "Hey what are you going to drink this weekend?" Naturally it followed with replies of this and that. Then someone sends "I'm drinking Bud!" and we all flame him out of fun. But some did not appreciate: A Microsoft employee sent "YOU GUYS SHUT UP AND GET BACK TO WORK". My pal Clayton then flames him with "Shut your cake hole you Nazi bastard", and then he asks me to help him take the guy down. I do a lookup and discover the FTE is in fact a Director and I tell Clayton to apologize, and he does. But this FTE dick won't oblige and goes nuclear over my pal. For me, that's it, gloves are off, and I go for the win with a 9-page email treatise on "Why we have the right to talk about Beer". The FTE tries but fails to flame me or shut us up, and this single watershed event begins a new chapter of my life:

Immediately we set out to organize and meet for the first of many "Brew-Ha-Ha's", every 1st Friday of the month at a random building on Campus at 5 PM to share and discuss homebrew. This meeting would go for about 90 minutes and then we'd all repair to the Rose Hill Ale House (previously was the Irish Rose, and hence now called Pub 85). Within a year we form the first Homebrew Club on the Eastside of Lake-WA called the Cascade Brewers Guild (CBG), meeting at Redhook Brewery in Woodinville Washington. I am elected the first President. Except for myself, all the Club officers are Microsoft Managers, but this would yield in time. After 18 months we finally hammer out the Bylaws.

I was also the Club Webmaster. The Club Secretary was the Product Manager for Exchange; he set up Seattle's 3rd ISP called NWMarket, hung the server in a closet on the 42nd floor of the Columbia Tower, and I became the Web Engineer under him so the CBG could have free web hosting.

Just prior to founding the homebrew club, I had been teaching class at Redhook, essentially "Homebrew 101 & 102": "Beer History", followed by "Basic DIY Homebrew" lesson using Charlie Papazian's 3rd Edition of "The Complete Joy of Homebrewing" as the guide. The founding of the Club also hooked me up with a fine GF who was a National judge in the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP); between us we revised the curriculum into a night/week 6-weeks prep for the BJCP Exam. That was the first year. It was so popular that we grew into 8, then 9, then 12, then 14, then 17, 21, and finally 24 weeks – I kid you naught, we had the longest course in the country to become amateur Beer Judges. Half of all judges in Washington State came through my courses. The highest rank I attained was BJCP National, however through the years I had gained enough experience points to qualify for Grand Master. I was the first Beer Judge to promote FIVE taste senses in class: Sweet, Sour, Salt, Bitter, and UMAMI. I was the first beer judge to break from traditional albeit pedestrian teachings of the AHA and instead used professional level Food Sciences & Biochemistry texts to better explain Fermentation, metabolic pathways of Alcohol on Digestion, and other related subjects. Through our sponsors I was able to expand our study of Water, Hops, Malting, and Yeast by having industry leaders as guest presenters to explain in fabulous detail about their subject of expertise.

For those that know the inside joke: "It's a cook book!" 😃. I wanted to touch upon another path of activism that I have really enjoyed and that is volunteering to serve at Beer festivals. The trait probably comes from the countless selfless acts of servitude during Boy Scouts; I just like doing the good deed and I am happy about it. Plus I am on the stage so to speak and get to talk about something that I really enjoy. My preference out of habit is to serve the earliest shift that I can get because:

- I get into the Fest for free

- The Shift usually lasts 3 to 4 hours, which leaves plenty of time to play later

- The opportunity to pour for someone new and learn about their craft; always a treat

- Afterwards I am free to wonder, social butterfly that I am to mix and connect with pals

- And sometimes if I am lucky, I'll get a free pour

- The After-Party: Very important if there is one.

I typically worked the Fest Circuit in and around the Eastside of Lake-WA: Herbfarm (remember those?) which later morphed into the Washington Brewers Festival, Caskfest, and Fremont Oktoberfest.

We held our first Homebrew Competition the Saturday prior to St. Patrick's in March 1997 at Redhook, and named it the Cascadia Cup. The winning beer was a "Columbus IPA" reigning in at 100 IBUs. Redhook brewed 100 bbl. and distributed it under a guest tap, thus launching the long-standing tradition that Best-Of-Show winner always gets brewed. I managed this competition for 10 years, including the fostering of Sponsorship. By 2006, we were the largest industry sponsored homebrew club with 37 signatories. In the last year that I managed the Cascadia Cup in 2006, the top 3 winning beers were selected by professional brewers on the BOS Panel for replication; a heck of a legacy and a testament of Club & Industry cooperation.

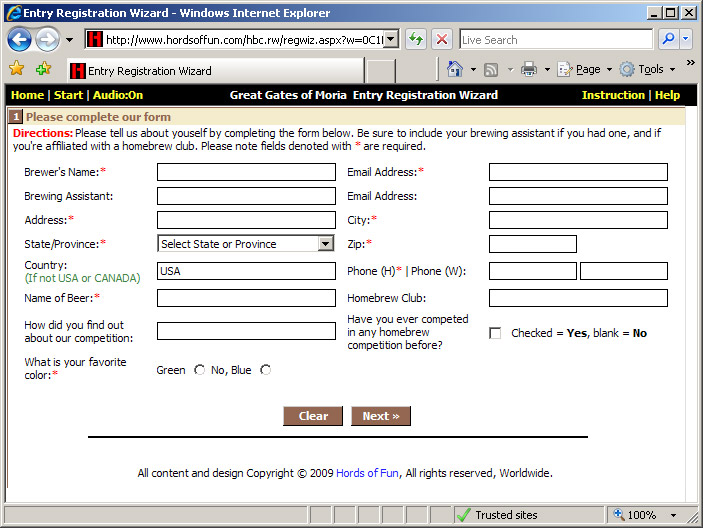

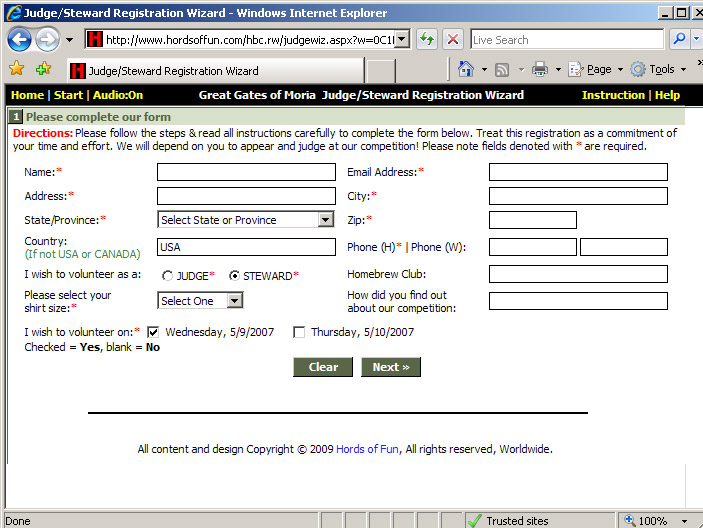

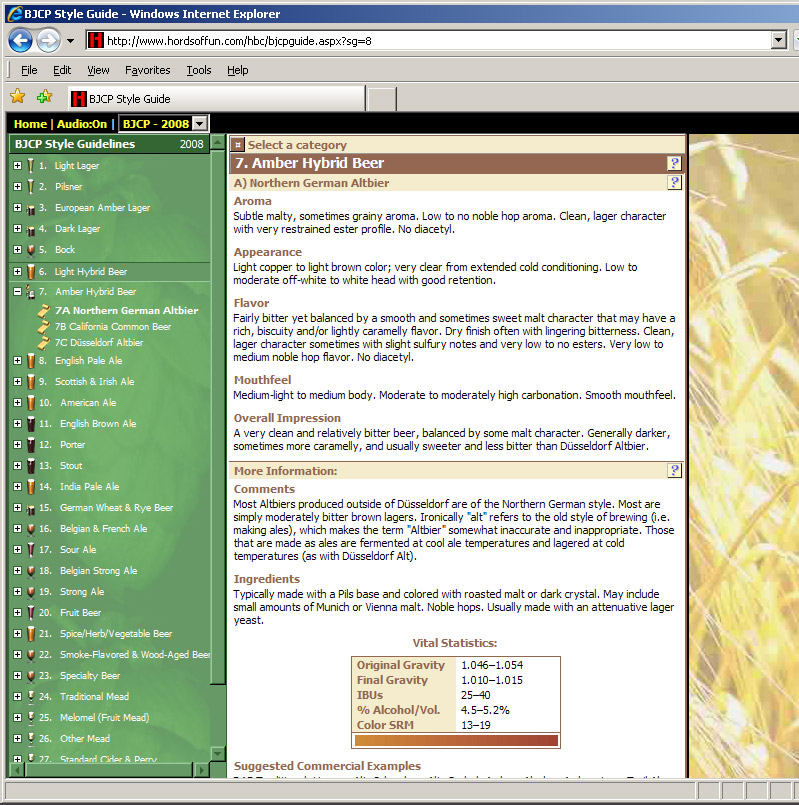

The first competition was traditional, meaning we gathered paper-entries: What a nightmare! I resolved to create the very first online registration system and used ASP + SQL Server for the database. This proved to be very useful and popular with other clubs wanting to use our system, but as it was written this meant giving up source code. Instead I created a new online Homebrew Registration System in the year 2000 that provisioned registered competitions, including registration of Judges, Volunteers, and Contestants, in addition to providing reports, results, and even custom award certificates. A standalone component – the online BJCP Style Guidelines was broken out as a separate reference application and still works today to display the 2004 and the 2008 guidelines. (Caveat: No further updates are planned).

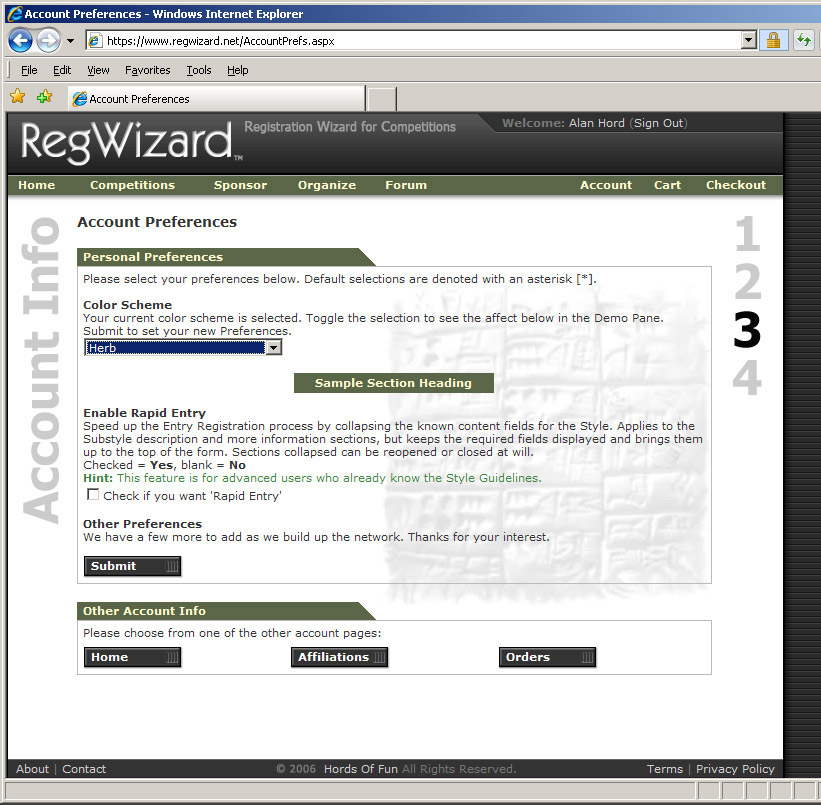

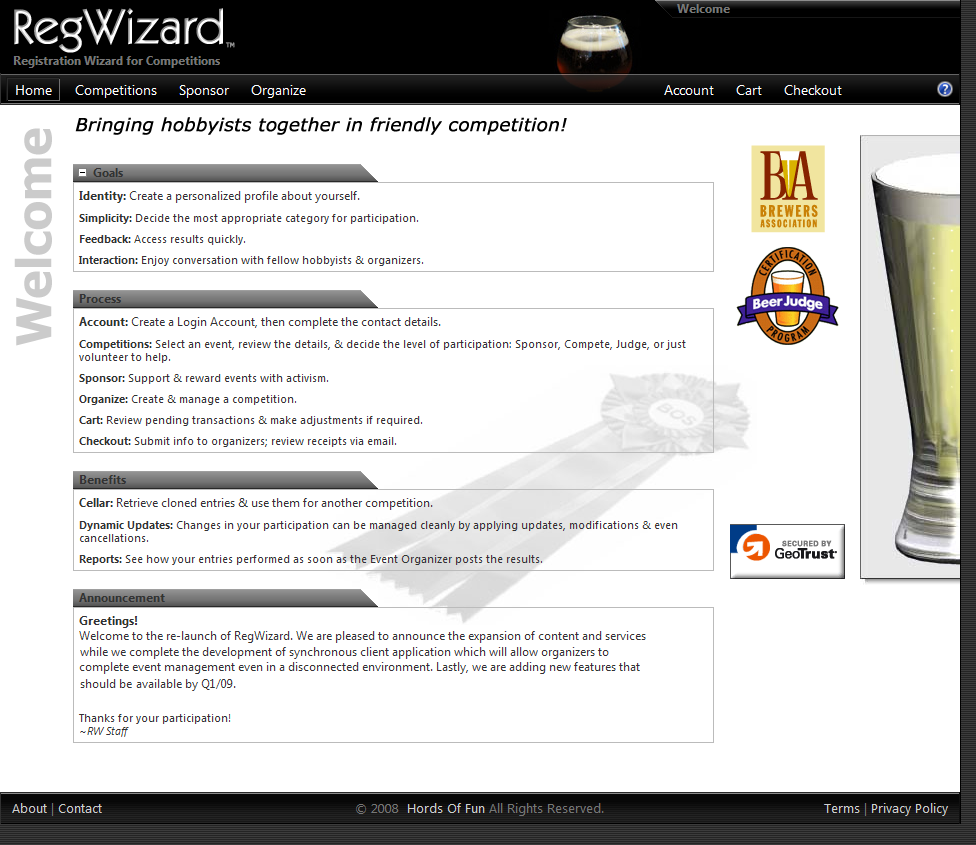

In 2004, I upgraded the entire solution to CSharp .NET and renamed it "RegWizard": This system was used for the first-ever online registration for the World's largest beer completion, the American Homebrewers Association Nationals. I was honored and count myself lucky to have a seat at the AHA Nationals Best-Of-Show table two years in a row in June at Las Vegas 2004 & Baltimore 2005.

The AHA Nationals uses two-rounds: 10 separate Regional events with the winners going to the Final round at a city which rotates around the country. The Northwest Region for years had been held in Portland Oregon. Eventually I was able to coax that event up to Seattle and managed that one as well for a number of years using online registration. The Cascadia Cup & the 1st Round Nationals were at that time Washington's largest beer competition, averaging over 200 entries each.

Competitions cost money to produce. Plus we wanted to have gift incentives for winners. In the Not-For-Profit Organization model, this means we must do fund-raising, and the best way was to solicit Sponsorship. Here's how it works:

There were back in the day about 28 Styles and 98 Substyles of Beer, Mead, and Cider. We target a potential client with sponsoring of a substyle fitting their business. So someone like Mac & Jack's would sponsor American Amber, Diamond-Knot might sponsor IPA, Sky River Mead would sponsor Semi-Dry Mead, etc.

Next is the money: Each sponsorship cost $100/year. From that we gift $30 to the winner, $20 to 2nd Place, and $10 to 3rd; there are no ties. The gift certificates are redeemable at any sponsoring homebrew supply store: They treat the cert like cash and remit them to us weekly, and we cut them a check back. Simple math says there's $40 left over: This goes to the General Fund that pays for Advertising, promotion, glassware, rentals, printing services, Guido & Luigi – our local Italian Mafia (just seeing if you're paying attention – 😃)… and most importantly – the catered food.

Some Sponsors elect to contribute schwag in addition to paying the fee – which is like going to Disneyland for us because it gives us a lot more wiggle room for awarding prizes. But the best and biggest prize of all is having a Best-Of-Show (BOS) Winner brewed by a professional brewer.

In return for the Sponsorship, one of the nice things I did was to create an Ad Banner that was placed at the foot of our Club Website pages and this rotated every 90 seconds. The advertising was exclusive and targeted our active club members. Click the button below to see this huge list of Sponsors that we collected over a 10-year period.

Near as I can tell, we were the largest industry-sponsored homebrew club in the world with 37 active sponsorships (with over 50 recruited). I personally brought most of them to the negotiating table. And I used my time to volunteer at Beerfests to specifically target new sponsors. In all, this was a very rewarding experience for everyone involved – except perhaps for those fighting to sponsor IPA – 😃

Briefly, this is a competition of another type sponsored by Wynkoop Brewing in Denver Colorado that begins with a Beer Resume. "The Beer Drinker of the Year is not only someone who enjoys, appreciates (and drinks) beer, but knows a great deal about beer, how it's made, its legend and lore and can demonstrate the range and depth of their beeriness." – Brewpublic.com. I qualified for Runner-up in 2006 and was a shoe-in for 2007, but as the year unfolded so did this. It is however worth noting because most people don't even get that far. Two officers of the CBG were winners of BDotY.

I took a job at Microsoft in 2005 that after a year I would be forced to take a mandatory 100-day break. Turns out that break would coincide with all of 2006 Summer. I planned from the beginning to take an adventure, not for 2 or 3 weeks, but for 36 days to Europe with the goal of visiting cities and sites of great beer. And I did, going to 7 countries, 22 cities, and drove myself solo over 6 km. I kept a copious journal of notes about each city, the travel, the food, and of course – the beer and the types of glass it was served in. Imagine this journey begins by flying into the Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, picking up a car and bravely getting onto the motorway without a clue to where next – 😃. No bitchy-sidekick; I was free! Briefly, some of the cities…

Amsterdam: Capital of Netherlands. Heineken tastes great; not at all skunked. Smallest room I ever rented; glorified expensive closet. I left a day early because of noisy construction outside my window. However the Rubens and Van Gogh museums were worth it. Bruges Belgium: Great medieval walled city with lots of good food and beer. Aachen Germany: Old cathedral, ancestral home of Charlemagne, super friendly people. Cologne: 9 Kölsch breweries, and one heck of a Cathedral! Düsseldorf: Hijacked at the first pub by the friendly crowd and treated quite well; had to stay another day to make up to the lost time with many excellent Alt-style breweries. Münster: Pinkus Brewery put me up for the night; two of my all-time favorite beers is served here – the Pinkus Alt and Urbock. Bremen: Another smallish city with excellent food and beer.

Three days in Berlin: Capital of Germany. Two fine breweries just over the other side where the wall used to be. The American-quarter reminded me of Berkeley California. Görlitz: On the border of Germany, Poland, and Czech; check out the little artisan brewers. Dresden: Capital of Saxony. Beer was not that great, but the 500 year old church was just restored and open again a few weeks prior and the palace grounds were something else! Prague Czech: Capital of Bohemia. Oldest brewpub in Europe right here and it was awesome! Lots of good beer here, plus very scenic, and loaded with friendlies! Bamberg Germany: The halfway point of my adventure with 10 breweries + I had Oktoberfest here; one for the bucket list! Vienna Austria: Capital of Habsburg Dynasty. Not so great beer, but the palace grounds were splendid. Hallstat Austria: My holiday within a holiday in the Austrian Alps where Yosemite meets Skagway; beautiful.

Three days in Munich: Capital of Bavaria. Best selection of beer in Germany bar none! Baden-Baden: Fun pub city. Frankfurt am Main: Capital of the HRE. Actually – I went across the river to Sachsenhausen where there are more pubs packed into 3 fun blocks than you can imagine and each one has their own beer! Brussels: Capital of Belgium and the EU. One place does it all – the Delirium Café. I was there for 2 days and had the time of my life.

It would take me 6 weeks before I could stomach American Beer after this trip because it was so overtly obvious that European Beer was much more balanced and enjoyable to drink. Sadly today when I go to a pub, it is mostly over-hopped IPA and Imperial this or that. I would love to go to Europe again though. Most people were very friendly and many spoke good English. The adventure had me fully recharged and raring to go.

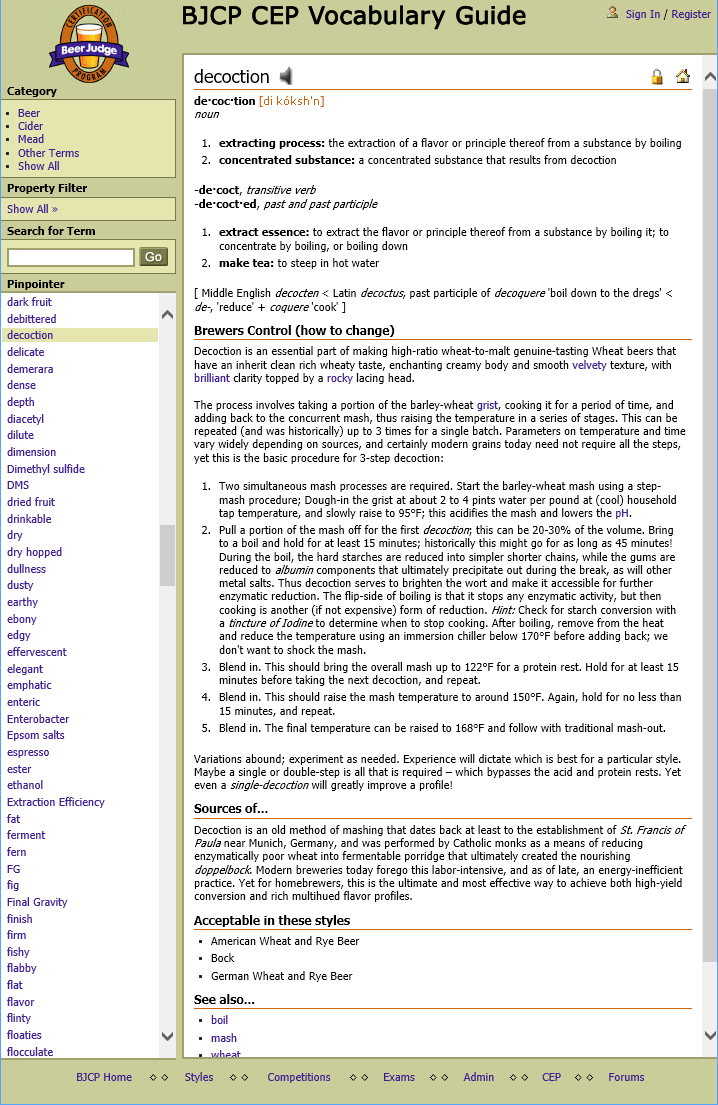

About 2003 was the year I became involved in producing a BJCP Vocabulary Guide: Think Microsoft Bookshelf, the online and CD-ROM Dictionary which I also architected and managed back in 1997. For the BJCP, it started out as an idea to canvas common terms used to describe the 14 off-flavors and beer faults in an attempt to standardize commentary on score sheets. I volunteered to create a prototype and used .NET technology for this. However the BJCP were LINUX geeks and wanted that for the final solution; they tried but failed to source programming talent that could take on the project. I didn't want to see this idea fade so I offered to develop and host the application on the HOF domain which I did for 3 years. We had in our charter 1500 preapproved words. With a coalition of 10 contributors we had cranked out 500 meaty definitions in that time.

However, as what frequently occurs in all-volunteer organizations where no one is paid and there is little professional oversite, the project bogged down into a political football with top-management over the quality of content at a time when we're trying to raise the BJCP from amateur level teachings to more aligned with contemporary professional curriculum taught at Seibel Institute and UC Davis. When the Vocab project was canceled, my interest in beer judging began to wane.

In addition, the CBG had recently rotated officers and new blood was elected into President, VP, and Treasurer. After my initial stint as President at the founding, I became the Club Secretary which mapped well with Webmaster. It turned out that the new Pres and VP had deep roots in Miller and AB. In September 2006 just after my return from Europe, these guys manipulated members of the Club to create an unpalatable situation – and I had to walk away. Further, the officers disemboweled the Sponsorship I had built in lieu of becoming a Budweiser-owned homebrew club. Can you imagine it? I can't. The whole point of making homebrew is to embody a freedom of choice and create any style we want in a manner of our choosing.

Today – for my part, I enjoy drinking beer at the consumer level without having to be "required" to taste every new beer out there. I do in fact seek and appreciate fine pilsners frequently without having to bear witness to petty stylistic diatribe when I can drink what I want! How liberating to be unshackled by petty beer Napoleons. But I am glad for the experience nonetheless because beer judging did give me one lasting effect: Sensitivity to sight, taste, and touch, and putting the right words to what is sensed. Fact is we judge continuously about all things, and I am better for it because I have words to describe those judgements in fine pleasant detail. Let's face it: I love to talk about beer and to brewers.

In addition, I have developed many lasting friendships and associations by traveling around the country judging beer, from Seattle to San Francisco, Anchorage to Baltimore, Las Vegas to Orlando, Portland, Sacramento, and many other points in-between. It is a very small world indeed and made smaller still by the kindred brothers and sisters in-beer and brewing, just having that friendship, insight, and sharing of a very old craft.

Finally, I am in beer-heaven: There are no less than 6 brewpubs/breweries in Redmond now, all easily accessible by walking or bike. We have more breweries in Washington State than in California, Oregon, and Colorado. That said I do not drink beer every day. If pubbing, I walk because it's not worth driving and having trouble find you. So my parting message is: "Imbibe responsibly. Take care of yourself; you only have one liver. Write down what you like and share. Read, read, read, then drink and read some more. Don't get too serious; it's beer damn it – so enjoy and have fun."

Cheers!

This section goes into more detail about beer-centric products that I have created since I became evangelized and active in the brewing realm at large. Some parts might sound like I'm repeating, though I'm not.

1998-2012; born 1998, re-released to public in 2000, updated in 2003 & 2007. It all started here back in 1997 after we organized and managed our first homebrew competition. The purpose of a competition is to fairly evaluate a contestant's entry as appropriate to style/substyle, to provide positive constructive critique, and to scale their standing against other contestants. This evaluation was accomplished by qualified judges, and served by volunteers. The caveat to this process is that the contestant cannot evaluate or serve their own beer and therefore cannot influence the outcome of the contest. This becomes problematic when dealing with a mountain of entries and associated paperwork.

However, if we can get these people to complete their application online (still fairly new concept in its' inception at the time), then we can use a programmatic approach to quickly build qualified panels and reports, and that is the heart of the solution. I was the first person to solve this problem in 1998 and it was entirely exclusive to my club, the CBG. Within a couple of years other clubs approached me to share the application, particularly our kindred cousins – the Oregon Brew Crew. However in the present incantation this would not have been possible without giving away source code, therefore I rewrote the entire structure to make it so anyone anywhere in the world could register their event and use the application albeit online. In return, the BJCP awarded me 0.5 points as a "registrar" for facilitating this service. In 2003, I again revised the entire system, upgrading to .NET and renaming it "RegWizard" for the explicit purpose of managing the worlds' largest beer competition: 2004 AHA Nationals. The eventual goal was to monetize the application for professional events such as the GABF, but my interest in beer judging declined quickly after 2006.

This application never collected entry fees; we only managed registration, facilitated the event through production of pull-sheets and panel management, by providing reports of results, and even insofar as producing award certificates. All of our competitions were sponsored, and the sponsor's name/logo would appear on the final results, score sheets, and award certificates. The presentation of records looked very much like Excel Online if it were hosted in 1998; though it would look clunky by today's standards, back then – it was ground-breaking because you could do sorting and grouping special filtering. It was really cool, feature-loaded, and I used every hack in the book to pull it off. Definitely a high-impact resume piece of work because just about everyone likes beer and can understand the concept managing "big data".

There were competing applications but they were nowhere near the level of sophistication, and one unsavory guy even used my online registration but then exported the data as tab-delineated text into their wacky setup. Is that rude or what? Plus, there was the ever-present circle of BJCP vultures trying to steal my source code which is part of the reason why I kept improving and securing it. A lot of this effort paid off in unique contracts at Microsoft.

Ultimately, the application was retired in 2012, mainly because I had retired from beer judging in 2008. At that time, I blocked new registrations, deferring them back to the BJCP, and maintained access to existing records for 4 more years. I was very honored by the patronage of those that it helped serve.

1998-2012, updated several times. This project was actually part of the original online registration application (as explained above) that I wrote back in 1998 and updated to .NET in 2003. It has been very popular as a reference. Some notes:

- I could never get the BJCP on board with providing an XML version of the Style Guidelines each time a new version was released. This left it to me to convert and import into a database; a very tedious process.

- The early versions of original content were inconsistent and in a few places with typos; they're all corrected in the online version and blessed by their agencies. In addition, there were very strange "subjective humanistic rules" regarding substyles that proved to be a programming challenge for presentation.

- The "tree control" on the left side is pure JScript, one of the very first in its' day and proving that I could architect the "control" and have it functional on any browser.

After 2008, my interest in beer judging came to an end, and there was zero incentive to carry on and maintain the product. As with the previous application, this was retired in 2012. It would have been impossible to continue to serve it forward because the tech I used to create the app was now very old and would require a complete overhaul at a time when I just didn't have the heart for it, especially considering the estranged relationship with the BJCP upper management. However, I was very honored by the patronage of those that it helped serve.

2005. Briefly, the original logo looked like a FAX of a FAX of a badly dot-matrix printout. About 1996 it was finally cleaned up a bit (shown below). With help from my Graphic Design buddy we reworked it into a savvy contemporary logo. However, after the fallout from the Online Vocabulary Guide, the BJCP sued to have me remove that logo from my website – the one we made and gifted to them for free. Then they changed it to the fugly thing that you see today. However, for a few years at least we had a tasteful design in place – and that I am proud of.

On the left, a nice B/W update from the 1997 Style Guidelines; we used this as a guide. Middle was our new version created at the request of the BJCP so they could have them embroidered onto white shirts. The Right was for the Website. Click on the button below to see what they reverted to.

BJCP Website: Other than the logo, that layout hasn't changed in 15 or 20 years. You'd think they'd get a clue…

2003-2006; prototype, and .NET production model with Content Management, Revision-Tracking, & Peer Review. It's been 10 years of silence; time to tell the story. Please accept that I was very proud to be part of this majestic influential project that started as a ways and means of getting all judges to use the same lexicon when evaluating fermented entries, plus it had the double advantage of becoming an excellent reference for identifying beer faults and fixes. The foundation of the guide circled around the 1500 words that were culled, approved, and vetted by the AHA and BJCP, and primarily based upon the words used in Michael Jackson's books as well as several other well-regarded industry intellects. Content was initially based upon the AHA series of books, however in short time it was apparent that much of that body of information came from a pedestrian point of view, e.g. one homebrewer to another rather than from a professional and clinical perspective. This is where our mutual committee of contributors began to run afoul with the BJCP: In truth and to be fair, I believe that the Upper management were beginning to feel marginalized or perhaps exposed to having insufficient knowledge in the germane of subjects; we're not entirely sure of the source of discontent because it was never explained.

Regardless, the original content was insufficiently thin if not altogether missing with regards accuracy and explanation. For instance, (and I greatly thank the AHA Forum for help in solving these riddles): The correct conversion between ABV and ABW, the difference between Melanoidins and the Maillard Reactions, the accurate portrayal of metabolic pathways when consuming alcoholic beverages, the profoundly damaging effects of Oxidation, the fifth Taste Sense Umami and its' importance to understanding glutamate… You know: BASIC STUFF if you are serious about judging.

The Contributors and Participants in this project were of the highest caliber and (if memory serves me correctly) at least Master-level Beer Judges. It was a really neat group of very intellectual and sophisticated experienced judges from all walks of life. The conversations we'd have during this endeavor were illuminating, and I felt much honored to work with these folks, these friends from across the country.

The technology behind the presentation of the Vocab project came from direct experience at Microsoft where I architected the common control for Bookshelf, Encarta, and Virtual Globe to work both as CD-ROM desktop application and online in 1997. Back then I had a team of 10 software developers plus 14 direct reports as the Technical Program Manager to produce Bookshelf. Six years later I single-handedly wrote the prototype and production version using .NET. Each definition had these basic properties:

- Title/Name of the term

- Phonetic and Audio Pronunciation

- Synonyms, Antonyms

- Etymology plus lore if known

- The Definition (one to many)

- Example of Usage if appropriate

- How found and corrected if a fault

- Association with style or class

- Related terms and external links

Images and formulas were included, as might a counter-point if the term was under contention (we tried to avoid those). What I really liked about the project was that we were actually making a difference with each monthly installment and had developed a kindred following.

The image of the application that you see is just that – an image. You can thank the BJCP for scuttling the project and threatening my livelihood. They never paid us one red cent or provided any other compensation for our efforts. If you are curious, please ask why they never gave us credit for the 3 hard years we worked to produce 500 quality definitions. Ask them why they sued me to remove the BJCP logo from the Hords Of Fun domain. Ask them why they had a problem with the Vocabulary Guide, and then ask them WHO WAS IT that had the problem back in 2006. When you get those answers – if ever, you will uncover a truth about the perturbed provincial minds ensconced in unelected positions of power and the real corruption rimming that inner circle. I have little sympathy towards ungracious people that behave without professional acumen, and the worst clients are the ones that never pay. This is why I retired from the BJCP, though not from Beer-Appreciation at large: That they can never take away.

But let me tell you how I really feel… 😃

2004-2012. This was the last update and rewrite of the Online Homebrew Registration Wizard (previously discussed). It had a completely redesigned backend, and was structured with a business layer of rules so that the presentation could be more easily ported to different end-clients. The ultimate goal was to monetize registration of for-profit professional competitions such as the GABF. It inherited all of the features of the previous online registration versions, however the performance of this last version was exceptionally quick, and included personalization and subscription. The eventual goal was to create a standalone client that could work remotely then sync to online when connected.

In addition and as the domain says, it promotes Registration through an online wizard, and not entirely restricted to Beer: I was approached by Wine people to do what I did for Beer with their industry. A lot of groundwork was put into that, but the sticky wicket was how do I get paid for this effort; how to monetize. Everyone liked the idea of registration wizards, but not how to pay for it. The wine people attested to be the stingiest collective, though you'd wonder why. The estrangement with the BJCP proved to be the undoing of my good will to volunteer or provide gratis services. What can I say? I need to feed my face just like everyone else.

The application was retired in 2012. Once more, I was very honored by the patronage of those that it helped serve.

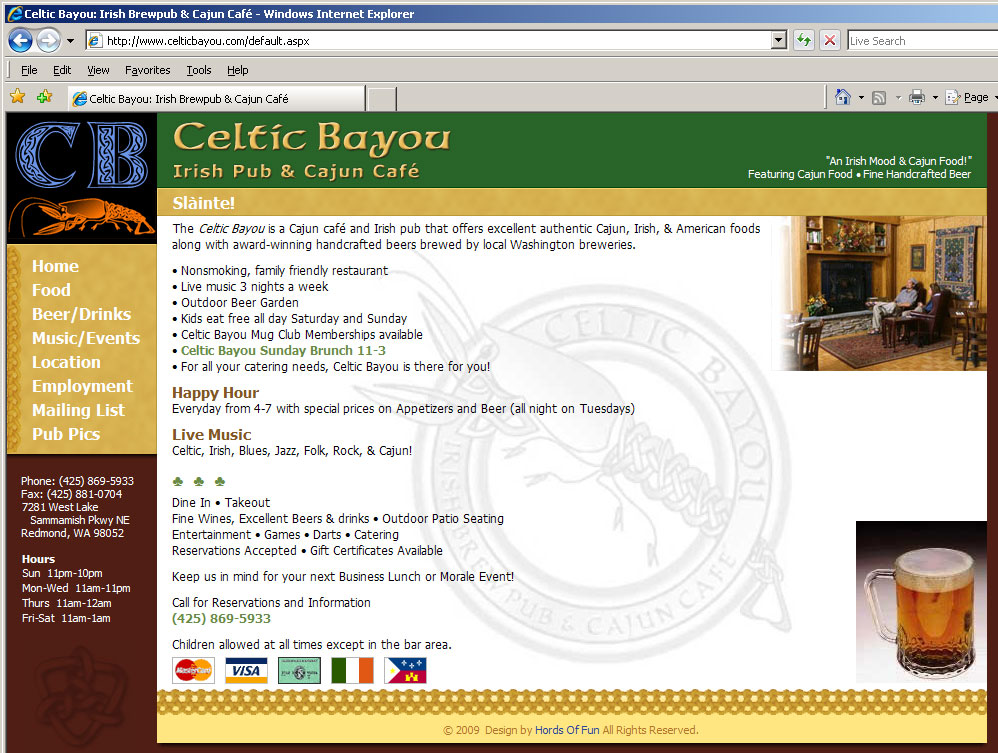

Year 2000: The Celtic Bayou and associated Far West Ireland Brewing Company opened in the year 2000 as a brewpub on the corner of West Lake Sammamish and NE Leary Way at the westbound onramp to SR-520 in Redmond Washington. The website specifically catered to the restaurant-side of the business, with featured pages of the Menu, the Beer, and Schedule. I wrote the whole thing in ASP before .NET and it included a content authoring tool. I knew that the owners could not afford to pay for the site with their money tied up in the brewery so I struck a deal with them: One free dinner + two pints every week in perpetuity, and transferrable upon sale. In truth, I was rarely there more than twice a month because I didn't want to abuse the nice setup; they were my friends and I just wanted to play nice nice.

The Celtic Bayou went through 3 ownership changes before the Moroccan owner (I forget his name) snapped it up. He proved to be a deceitful cretin, too cheap to agree to the deal, and he presumed wrongly that he owned the source code even though his contract only included the domain name and nothing else; I had the copywrite & ownership statement clearly at the foot of each page. Because he refused to honor the deal, I refused to update the website. He even tried to recruit local software developers to reverse-engineer it, however all they knew me and nicely refused. The stalemate ended when after 3+ years he finally footed the cost for a complete redesign. I heard recently that the Celtic Bayou was sold to another foreigner and then it strangely caught fire shortly thereafter which is very odd considering that at the time of construction the kitchen was up-to-date to the newest city code and rigorously inspected before opening. It is a mystery.

Fall-2016: Brickyard is based in Woodinville and is owned by my mutual friend and business partner in another adventure. He asked me to produce a website for him after his recent expansion into North Bend with a caveat that it has to be very simple to maintain by his staff which may or not be tech-savvy. The primary features of the website are: Traditionally Featured Beer, What's on Tap at North Bend, Food Specials, the Social Event Calendar, Distribution, and finally Location and Hours of operation. The interactive feeds are Taphunter and Facebook:

- Performance was a problem with client devices pulling from Taphunter every time they visit the page, so I changed the architecture to have the content cached in SQL and updated every 90 minutes. Changes to the website are reflected every time the Bar Manager updates the list.

- With Facebook, I used the API to pull the Food and Events twice a day. Changes here are made every time the Chef posts new food or when someone updates the social calendar. It's really slick and dead-simple.